Andy Warhol once said “everybody has his fifteen minutes of fame”. Mine perhaps came after the 2001 national elections when my predictions for the election, published in The Daily Star six months earlier, turned out to be accurate. The results of the elections took most people by surprise, as for the first time we saw coalition politics in Bangladesh parliamentary elections. The article I had written was in fact the summary of the presentation I had made to the BNP Chairman two years earlier. I had joined the BNP in 1978 and was elected to the 2nd Jatiya Shanghsad in 1979 on a BNP ticket. I again contested in 1991, but was not elected. That year I retired from the Party and all political activities. I did not meet Begum Zia throughout her first term as prime minister, but met her soon after BNP lost the 1996 elections. In that meeting I advised her not to worry about the defeat, but that she should go to parliament, make her policy statements, and hold the government responsible for its actions. The party had a sizable presence in the House, and she should use this to consolidate democracy in the country

I next met Begum Zia three years later. Mr Moudud Ahmed had rejoined the BNP. He had lost the bye-election to the Laksmipur seat vacated by Begum Zia, and after a book writing sabbatical to Europe, returned to look for ways to bring the party back to power. He was among the few in the party who thought in those lines. One of his first steps was to try to get what were termed as “nationalist forces” on to one debating platform. In essence these were anti-Awami League forces. A series of seminars were held under the banner of a national solidarity front where participants included the Jammat-e-Islami. However, this did not go much further. In 1999, he asked me what BNP needed to do to win the next elections. I told him that they needed to firm up the anti-AL forces into one electoral platform and contest the elections by sharing seats. I pointed out that people voting against the AL are more then the people voting for it. If the anti-AL votes were not divided, the alliance could win by a landslide.

The concept of Anti-Awami League Alliance

I had been studying election results for years. In fact I selected my parliamentary constituency in 1979 based on this theory. After joining the BNP, I visited my home district of Sylhet to organise the party for the forthcoming parliamentary elections. I did not know the district well, and since I was expected to contest, I scouted around for a seat. My ancestral home was in a constituency comprising two large Thanas with high voter population. It would be a difficult and un-wildly constituency, not easy to make it a “safe” seat. I chanced upon a small constituency in the north of the district. Though it also comprised two Thanas, they were small, and the number of voters was much less. There were few capable local rivals and the voting population included large numbers of people from other Thanas of the district as well as other Districts of the country. Many of these people were settlers that had earlier gone to Assam in the 1950s but were later driven back. Records showed that the Awami League had won this seat in 1970 & 1973. However, this was with a minority number of votes and the majority voters had voted against the AL. But these votes were split over numerous candidates. I felt if I could consolidate the anti-AL votes, I could win this seat. The BNP leadership were a little sceptical about my choice as they did not think it a safe seat. Nonetheless, I went ahead. There were ten candidates in this seat in the parliamentary elections of 1979. Of the 44,290 valid votes cast, I got approx 14,000, the AL candidate 10,500. Though I did not get the majority of the anti-AL votes, it was enough to prove my point.

The BNP did not contest the 1986 election and so I was not in the race. One of my school friends, who had helped me in my previous campaign, took the opportunity to contest on an AL ticket. In that year about 41,000 votes were cast and the AL won with approximately 18,000 votes. 23,000 other votes were split among three other candidates. I was again a candidate of the BNP in 1991. My friend was the AL candidate. I was confident of winning as I pegged voter turnout at around 55,000(due to increased voters). I expected the AL share to be around 20 to 22,000 and the majority to come to me as there were only four other candidates of little consequence. This was the trend till a week before the election. Neither my friend nor I were “locals”. My friend’s advantage was that the AL was well organised with a minimum base. The BNP (basically myself) had been absent for two interim elections, and as we were involved in agitation politics (mainly city based), the party organisation was weak. I was approached by “local” students to “buy” out my “local” rival. I did not see any necessity as that person had only got 597 votes against me in the previous occasion. But the first Gulf War would change that in Sylhet. Two weeks before the elections, a lot of local sympathy developed for Saddam Hussein. A lot of this sympathy transferred to Ershad’s Jatiya Party (perhaps as an underdog), and in its absence, to “local” candidates. Before my eyes I saw my base erode, but I could not do anything about it. The results showed a casting of approx 54,000 votes (35% approx, against a national average of 55%). The AL got around 23,000, while I got only 14,500. My “local” rival ran away with 13,000 votes. The AL base was as expected, but I was unable to consolidate the anti-AL vote.

In 1996, my friend was again the AL candidate. The BNP candidate was then Finance Minister Mr Saifur Rahman. Votes cast was approx 93,000 or 62.5%. The AL got 22,725 votes. BNP won with 23,946 votes. Though the number of votes cast increased, it was spread over eight other candidates (The BNP together with AL getting only 50% of the vote). Mr Saifur Rahman gave up the seat as he had also won from Moulovibazar. In the bye-election to this seat, the votes cast dropped to about 35%. My friend on the AL ticket got 23,634 votes (same as 1991) with the BNP candidate in 3rd place with 9,664 votes. This in essence was my theory. The AL has a core vote, in most constituencies of 30% to 35%. If the anti-AL votes could be consolidated, the AL could easily be defeated in most seats.

The theory of an anti-Awami League vote bank is a peculiar phenomenon. The question begs to be asked is why a popular party that brought independence to a nation has such a formidable section of the population against it. The answer lies in BAKSAL. The Awami League’s imposition of one party rule with all its appendages alienated the then major section of the population, forcing AL to spend the next two decades trying to make amends. It would be the entry of a new generation on to the voter rolls, coupled with an inept government that would bring the AL to touching distance of power in 1996. A provision of “winner take all” reserved seats for women would then consolidate that Party in government.

Theory of the Alliance

In mid 1999, Mr Moudud Ahmed asked me to explain my theory to Begum Zia. I presented my theory of electoral patterns and suggested that were she able to form an alliance with the Jamaat-e-Islami and the Jatiya Party, she should be able to win over 200 seats in the next elections. She seemed to grasp the core of the argument. She then asked a few very pertinent questions such as, would in fact the vote of one party transfer to an alliance partner? In other words, would the Jamaat-e-Islami vote come to a BNP candidate in a particular seat and vice-verse? We needed to establish this. We also needed to know what the base support of the major parties was, and how much of the anti-AL vote could be consolidated. This would have to be done through field testing. I had this done by a very professional market survey company during June 1999, covering all the constituencies of Dhaka City. I did not have the funds for a national level study, but I believed that Dhaka would more or less represent the national average. The results supported our theory.

We found that the BNP, Jamaat and Jatiya Party votes were transferable. The base support of the parties was also as per my estimates. In other words, the signal was green as far as Begum Zia was concerned. Once again I made my presentation of the results of the survey. She had one more important question. Could Ershad be trusted? My reply was that the elections were two years away. If she could keep him with her in an anti-government movement for even a year, Ershad’s possible betrayal would only split his party, and more importantly, the JP voter would be opposition attuned and stay with the movement. I gave her a copy of the survey results. This would be my last meeting with Begum Zia. She asked for suggestions on which seats that BNP needed to keep and which could be negotiated. This was given. Initially, she was one of the very few in the Party who understood the concept of the alliance, and it is a credit to her political acumen that she pushed it through to its logical culmination.

Lessons of 2001 Elections

The results of the 2001 elections are known to all. Though I had expected the Alliance to get 200 plus seats, the votes received by the AL and the Alliance was a surprise to me. I had not expected the AL to get as much votes as it got, which was 41% against an Alliance total of around 47%. This meant that the AL had crossed the magic figure of 40%, and that the anti-AL vote theory would not work any more. The Awami League apparently had come out of its BAKSAL stigma. The majority of the 2001 voters were of a post BAKSAL generation. They had seen the two parties in government, and the issues were not of past politics, but one of governance. The Alliance was very lucky to get the number of seats they got compared to the votes cast in their favour. Unfortunately for the BNP, they have not understood this. They confused the number of seats won with actual votes cast. This is not so. Table 1 shows the actual voting for the main parties from 1979 to 2001. One will notice a steady rise for the AL as against ups and downs for other parties. Then again, only a 6% spread between the Alliance and the AL means that there will be a further shift in the base votes before a future election. 2001 elections was a watershed, and all calculations for the future needed to be done afresh

Survey 2006

To understand the present support base, and to make an “intelligent guess” (it is not possible to any better then this) at the possible results of the next elections, I needed a fresh survey of the voters. This was carried out during June of this year by the same organisation that did the survey in 1999, using the same methodology. The results were astounding. At first I wouldn’t believe it. I had it re-checked. The results were the same. The core base of every single party had eroded in a massive way. Table 2 shows the survey results of 1999, the actual votes of 2001, and the survey results of 2006. How and why did this happen? It seems that the voters are disenchanted with the whole political system. They had voted for the Alliance on the hope of better governance, and when they did not see this, they moved away. But why the erosion of AL’s base? They are not in government? The answer has to be that the voters do not have much expectation from them either. The core vote for the BNP has dropped to 16% while that of the AL to 23%. This is the lowest since the Presidential elections of 1978. The vote of the Jatiya Party has halved, while the Jamaat-e-Islam have two third of their vote base eroded. Interestingly, the vote pattern is similar among both sexes and through all age groups.

For the first time in our history, with elections less then six months away, more then half of the voters are undecided, i.e. not sure who to vote for. This indeed is an indictment of our political parties. One can only speculate as to what has led to this situation. As democracies mature, people tend to look more to performance then politics. For instance, in the UK, the core support for either the Labour or the Conservative party is around 25%. Support for one or the other increases on the basis of the voters perception of the Party’s performance, its policies and its conduct.

So what does the survey tell us? It appears Bangladesh is reaching a political maturity of some sorts, albeit for different reasons. Voters are now more discerning in their opinions. They are better informed through private TV Channels, the increased print media, both national and local, and the activities of “civil society”. They have the information, and are capable of judging for themselves. They feel let down by the political parties, including their own. Politics and slogans no longer appeal to them. They are fed up with inter party bickering, unbridled corruption, total lack of governance and signs of dynastic politics. They are also frustrated with their lack of a viable choice in a future election. This does not portend well for the future of democracy in the country. Thailand stares us in the face. My own belief is that, if a poll is taken after a “neutral” caretaker government takes charge, the majority of voters will opt for it to continue for some years to come.

What holds for 2007?

But the reality of the situation is that we are headed for a national election. We have some facts on hand such as past voting patterns. I will use those, along with conjecture based on my insight and assessment, to give my personal opinion of what may be the outcome of the next election, if it does take place on schedule. I emphasise again, it is a personal opinion only. Today there are many permutations and combinations of alliances, partnerships, understanding etc. We need to look at different scenarios, the parties and personalities in order to arrive at an “educated” guess as to what may be the vote pattern. Let us start with the Alliance. For all practical purposes it is the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party.

The original basis of this party was to provide a platform to General Ziaur Rahman to break from his dependence on the Army for support in the early days of this rule. The unstable days of 1976 to 1978, which saw a series of unsuccessful Army coups, necessitated this. The JAGODAL, and the subsequent Bangladesh Jatiotabadi Front were the predecessors of the BNP. These forces were an amalgam of freedom fighters, far right elements that had opposed the independence of Bangladesh, as well as far left revolutionary forces. After the Presidential elections of 1978, these forces were consolidated into the BNP. The Party never jelled. After the assassination of Ziaur Rahman, conflict developed in the Party over the extant of inner-party democracy. The Martial Law of 1982 temporarily kept the Party together, only for General Ershad to take away the major part of the leadership into his Jatiya Party. A small core was left to Begum Zia who had taken over the leadership. It was her championing of democracy, and the reputation and memory of Zia as an honest person that brought BNP to power in 1991. By then the party had begun to change as there was an influx of fresh members, mainly from the newly rich business community and the retired bureaucracy. Politics took a back seat to expedience. As a result, the Party did not pay heed to the popular demand in 1995/6 for a caretaker government system. Mismanagement towards the end of its tenure, including the fertiliser crisis saw the BNP lose support in its strongholds like Dhaka Division, which resulted in the BNP losing the elections of 1996. By 2001, there was another sea change in the Party with the entry of a wave of young persons of suspect education and background. Now the Party is devoid of politics. The capital that President Zia had given the Party with his exemplary honesty is spent. The talk of following his ideals mean little to the voter as the Party has been in power for ten of the last fifteen years and will be judged by its performance rather then anything else. The Party is now on the verge of another break, even if partial. This will have a major impact on the Party’s electoral fortunes.

There is, at present, significant differences between the old and new leadership. Mr Tarek Rahman is leading the new wave. He appears to be in command, but he has neither earned the respect and loyalty of the old Party members, nor inspired the “new” voters who are of his generation. To this is added the conflict in almost every parliamentary constituency between the seating MP and his rivals. Fuelling this conflict is the horde of “new comers” who have been associated with the Hawa Bhaban entering the electoral fray. Many of them are retired or retiring bureaucrats, who are now asking for their rewards. The BNP no longer seems to be a political party. It is rather an association of interest groups aligned by their sole desire for financial gain at national and local levels. This also means that the local inner-party rivalry is based not on political differences, but on economic ones. This further means that disciplining by the High Command will be all that more difficult, as the “economic” stakes are too high for the rival factions. The result is that almost every BNP seat is now “unsafe”.

The BNP’s, and particularly Begum Zia’s, election campaign seems to be based on a combination of its claim of development work, and the bogey of “foreign hands”. While it is undoubted that more development has taken place in the last five years than in the previous five, one has to see how the voters perceive this. Historically, from 1960, successive governments have done more development work than previous governments. It is simply that annual budgets get larger and there is more money to be spent. Ayub Khan and H.M.Ershad are two examples. But did they have immediate electoral benefits? Both had mass movements against them. It may be argued they were semi-military governments. Well, the last Awami League government did far more development work than the preceding BNP government. Did it reap the electoral benefit? To a voter, development work is lower on his priority. What is more important is the quality of life. Is he or she better off than before? Are prices of essentials higher or lower? Does he have better excess to power and water? These are the issues the BNP will face in the next elections. Than again, the bogey of “foreign hands” has been overused. In an absence of politics among the political parties, this is not a factor in our elections

For the BNP there is a further problem. Dr B Chowdhury has broken away and formed the Bikalpa Dhara. Col Oli Ahmed and his associates are also likely to soon part from the BNP. They will draw to their fold many other lesser dissidents to whom politics is still important. All this will cut into the Alliance vote bank. Consider the fact that in 1996 in Dhaka Division (84 seats excluding Gopalganj and Madaripur Districts), a vote swing of around 5% saw BNP lose 26 seats, while a reverse swing of 8% in 2001 saw them regain 26 seats. Also keep in mind that in 2001, in the same area, the BNP led Alliance with 44.68% votes got 56 seats while the AL with 43.19% votes only managed 25. A mere 1.48% votes separated the two camps.

Also consider some other facts. In 2001, the BNP won 26 seats with a margin of less then 5%, 41 with less then 10% and another 41 with less then 15%. That means a total of 108 seats are separated by a vote swing of 8%. The electoral history of South Asia shows that almost no incumbent government gets as much votes as that which brought it to power, even if their governance has been good. In the present situation, the BNP Alliance can expect to see an outward vote swing of up to 10%. If the outward swing is 4% from BNP to AL, the BNP will lose close to 70 seats. If the swing goes up to 8%, the BNP will be reduced to around 80 to 85 seats. Should the swing go as high as 10%, the BNP will have less then 60 seats in the next Parliament.

The Jamaat-e-Islami

The Jamaat is an old party, reputed to be well organised. I do not know much of this Party except that it opposed the Liberation War and that its aim is to see the establishment of Islamic law. None the less, as long as it is a participant of the political system, one has to accept it as a player in our democratic process. Its electoral fortunes have been chequered. It fought with other opposition parties against the Ershad dictatorship in 1989/1990 and seemed to get some reward. In 1991 it won 18 seats in Parliament with 12.43% of the popular vote. It participated in the anti-government movement of 1995/6. However, this time around in the elections of 1996, its vote share was reduced to 8.61% and seats in Parliament to only 3. It joined BNP in an alliance in 1999 and in the elections of 2001, it was allocated 30 seats. It contested one more independently of the alliance (Ctg-14). Table 3 shows the Jamaat seats in

2001, and votes obtained by them in those constituencies in 1991 and 1996 elections. I have held that the reputed strength of Jamaat is not based on ground reality. Between 1991 and 1996, it lost one third of its vote base. This was a dramatic loss. My theory is that the Party may have built up some cadres, but it failed to attract the general voters, particularly the newer ones who came into the voter lists in 1996. Though it won 2 new seats in 1996, it lost 17 of the 18 seats it held. In electoral terms, this was a washout, and my opinion is that, had there not been an alliance in 2001, the downward trend of Jamaat would have continued. In fact it did.

Even as an Alliance partner, the performance of the Party in 2001 is poor. Of the 31 seats contested by Jamaat, 10 had been held by them in 1991, of which they had lost 9 in 1996. In 2001, with the help of the BNP, they won back 8 seats. The other 8 seats, held by Jamaat in 1991 were not given to them as the Party was not strong enough in those seats. Of the 30 seats allocated to Jamaat, they lost 14. That is almost half the seats contested. Considering the fact the Jamaat had bargained for those seats based on their own assessment of strength, and the fact the Alliance was riding a popular wave, the Party indeed cut a sorry figure. Even more surprising is the extant of their miscalculation. In 3 of the 14 seats lost, Jamaat candidates lost their deposits, getting less then 10% of the votes. In 2 other seats it got less then 25%, in 5 seats less then 30% and in 5 more seats, below 40%.

The Alliance concept also did not work everywhere. A case in point was Jessore-6. In 1991, Jamaat won this seat with 47.13% votes. But in 1996 their votes came down to 16.27%. However, the combined BNP, Jamaat vote that year was 44.66%. The AL had won that seat with 35.04% of the votes. It was expected that in 2001, it would be a safe Alliance seat. Unfortunately, a BNP rebel contested and the AL retained this seat with 45.01% vote. The BNP rebel got 44.88% votes while the Jamaat candidate got only 8.45%. Another case in point is Moulavibazar-2. The Jamaat did not contest this seat in 1991. In 1996 the Party got 3.82% of the votes. The seat was won by the AL with 39.35% of the votes. The BNP came third with 23.43% votes. In 2001, unexplainably this seat was given to Jamaat. Its candidate got only 7.18% of the votes while rebel BNP candidate won as an Independent with 45.50% of the votes.

Even Jamaat stalwarts are not on sure wickets. The Ameer, Moulana Motiur Rahman Nizami won from Pabna-1 in 1991 with 36.85% votes. In 1996 he came a distant third with 23.92% votes. That year the BNP candidate came second with 33.20% votes. The combined BNP and JI vote in that seat was 57.12%. The seat was won by AL with 41.51% of the votes. In 2001, Moulana Nizami won with exactly 57.68% votes while the AL got 41.62%. In the next election, Moulana Nizami can win only if he has the full support of all who voted for him in the last election. As a member of the government, he has to share blame for its failings, the price raise of essentials, power crisis etc. It would be difficult for him to overcome such odds. In another example, Moulana Abdus Sobhan won Pabna-5 in 1991 with 47.31% of the votes. In 1996 he dropped to third with 19.63% votes. The seat was won by BNP with 41.10% votes. In 2001, this safe BNP seat was gifted to Moulana Sobhan and he won it with 56.78% of the votes. The AL was second with 41.13% of the votes. Moulana Sobhan faces the same scenario. What I am trying to demonstrate is that the Jamaat won almost all its seats only with full support of the BNP and its sympathisers. This is going to be a crucial factor in the next election as the Jamaat is weaker then ever before, and the BNP vote may no longer be solidly with them.

In Table 3, we see Jamaat core vote drastically reduced. In our survey, we asked the BNP voters if they would vote for a Jamaat or a JP(E) candidate as a part of the Alliance. 43% said no. Of the group that said no, 93% said they would like to see BNP contest on its own. While this is a mere opinion at the time of the survey, consider some other facts. Since 1996, the Jamaat has been absent from the electoral process in 269 constituencies. This is an absence of ten years. During this period there have been a vast number of new voters on the rolls. More the half the voters in the next elections have never seen a Jamaat candidate. As any student of constituency politics will tell you, a party can not build up a vote base if it does not contest in the particular seat. It is illogical to think that just because the Jamaat has been in Government, and has been able to give some of its supporters some benefits, its vote base will have increased. On the contrary, its participation in Government has hurt the Party. Jamaat sympathisers will ask where the Jamaat politics is, and what the Party gains from being in the Alliance with the BNP. A large section of its support base feels that the Party is deviating from its core objective, i.e. the formation of an Islamic state. This base has moved to the far right and has manifested itself in different forms such as the JMB. Again, the association of some Jamaat cadres with active militancy has alienated the traditional BNP support base and they will show this dissatisfaction through the ballot.

There is a myth about the Jamaat. Its public posture is one of supreme confidence. It is trying to pressure its Alliance partner BNP to give it more seats in the next election. The current BNP leadership are political novices and are stuck with the 2001 electoral numbers. However, the reality is different. The Jamaat have virtually nothing to give to the BNP. If the BNP accedes to the Jamaat demands for new seats, there surely will be rebel BNP candidates in those constituencies resulting in a loss to the Alliance. At present the Jamaat hold 17 seats. Over the last five years, the local Jamaat MP and the local BNP party have distanced themselves. In almost all these constituencies, the Jamaat MPs have concentrated on their own Party thus alienating the local BNP leadership, who have also been denied a share of the booty. This difference is now out in the open and in the national media. It will be next to impossible for the BNP leadership control this. It is my belief that in all likelihood, we will not see a Jamaat presence in the next Parliament. At best it can expect a maximum of 3 seats.

Jatiya Party (Ershad)

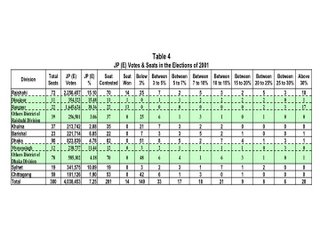

Jatiya Party was born in betrayal. It was founded by a man who betrayed his oath to uphold and honour the Constitution of the Country. It was, and is, manned by people who betrayed their own Parties at a time when their parties needed them the most. The Party has no politics except to be in power and share booty. It won two rigged elections in 1986 and 1988, but was ultimately forced out in 1990 through a popular movement. In spite of all this, it did get about 12% of the vote and 35 seats in the election of 1991. It joined the movement against the BNP Government in 1995/6. It was rewarded with a larger vote share in 16.23% of the votes, but its seat share fell to 31. True to its character, the Jatiya Party joined the BNP led Alliance in 1999, only to leave it in 2001. This led to a break in the party. The Jatiya Party (Ershad) as it has now became, formed its own group calling it the “Islami Jatio Oiko Front” (IJOF). In the elections of 2001, this Front halved its vote share to 7.25% and only 14 seats. Let us look at Table 4. For the purpose of this article we will presume that all the votes of the IJOF are that of JP(E).

In 1996 the Party had received 69.54 Lac votes or 16.23%. But in 2001, the Party got only 40.38 Lac votes or 7.25%. This was at a time when 133 Lac new voters had come on the Electoral Rolls. Of the 40.38 Lac votes that JP(E) got in 2001, Greater Rangpur accounted for 16.45 Lacs, which was more then 40% of its total votes. Rangpur also accounts for 13 of the 14 seats won. The other seat is in Dinajpur, where it got 15.48% of the votes. In the rest of Rajshahi Division with 39 seats, the JP(E) vote share was a mere 3%.

In the rest of Bangladesh, the JP(E) votes accounted for only 4.65%. In Khulna Division with 37 seats, the Party got 2.88% or 2,13,742 votes. In Barishal Division with 23 seats, it got 6.85% or 2,21,714 votes. Of this, 1,14,502 were in 4 Constituencies (49,109 was in one seat where M.R.Talukdar lost to Sheikh Hasina). In Dhaka Division with 90 seats, the Party got 4.78% or 8,23,839 votes. Of this, 9 seats accounted for 3,74,716 votes, leaving 4,39,123 votes or about 2.61% spread over the balance 81 seats. In Sylhet Division, the Party got 10.09% or 3,41,575 votes. Of these, 3 seats alone accounted for 1,05,044 votes with the balance spread over 16 Constituencies. In the 3 seats that accounted for a third of JP(E) votes, none of the candidates even came close to 2nd position, with the highest at 3rd position with 20.97%. In Chittagong Division, the story is even more dismal with the Party managing only 1.90% or 1,81,126 votes. Out of 52 seats contested by the party in this Division, in only 3 seats (two in Brahmanbaria and one in Noakhali) did they get more then 10,000 votes. It is interesting to note that the higher than average votes of JP(E) in some constituencies is due to the personality of the candidate rather, than support for the Party. A different candidate would not pull the same number of votes,

Consider other facts. Of the 281 seats contested by JP(E), it got 3% or less in 149 and lost its deposit in over 200. It only managed to get above 30% in 20 seats of which 17 were in Greater Rangpur. The question that now begs to be asked is how can JP(E) benefit any Electoral Alliance? Its vote base is on the decline and is concentrated in one district. In 2001 it failed to attract the new voters. It is illogical to expect it to do so in the next election. Then why is the BNP so keen to have it in the Alliance? I personally fail to understand it. The only explanation I have is that the present BNP leadership are getting the sums wrong. Then again, maybe I am making a mistake. So, let’s take another look. What is the profile of the JP voter? He or she is a person not happy with either the BNP or the AL. They want another choice. But the JP voter by inclination is opposition biased as they have been against different governments for the last 15 years. This time around it is no different. Their dissatisfaction will not be so much against the AL for their miss-governance the last time around, as much as it will be against the present government’s lack of governance. Incumbency, power crisis, raise in prices of essentials etc, will bother them as much as anyone else not in government. If that is the case, what is the scenario?

General Ershad must be having a great laugh. He is calling the shots for agreeing to join the BNP led alliance. He will ask for 40 to 50 seats. From where will the BNP give him the seats? In North Bengal, there will be a direct clash with the Jamaat. Of the 30 seats allocated to JI, 12 are in Rangpur and Dinajpur. Of the 17 seats held by Jamaat, 4 are in these districts. Outside of Rangpur, JP(E) does not have the base in any constituency to build into a winnable seat. Aside from the existing 14 seats, Ershad will be asking for BNP majority seats where he is not even a close second. For example, Ruhul Amin Howladar, the General Secretary of JP(E) may want a seat. In the last three elections he contested Bakerganj-6. The results were 1991 (18.77%), 1996 (15.58%) and 2001 (14.85%). The seat is presently held by BNP against the AL with a margin of 9.7%. Again, if Kazi Zafar Ahmed wants his seat in Comilla-12, he will be up against Dr Md Taher of the Jamaat who won the seat in 2001 with 66% of the votes. The AL was next with 33%. The IJOF candidat got 0.29%. Kazi Zafar had won this seat in 1991 with 35.78% of the votes. Jamaat’s Dr Taher was second with 25.40% (AL got 24.58% and BNP 9.69%). In 1996, he lost to the AL (46.49%) getting only 21% of the votes. The same Jamaat candidate got 24.27% and the BNP 6.78%. The Jamaat victory in 2001 was due to the total consolidation of the anti-AL vote which is unlikely to repeat again.

If the BNP sacrifices some of their majority seats to JP(E), there will undoubtedly be rebel candidates to ensure that all these are lost. Many in the rank and file of the BNP do not accept Ershad. One must keep in mind that a major plank of BNP’s politics has been its fight against the Autocrat. While the BNP’s leadership may overlook this for the sake of political expediency, others in the party may not do so. To them, and other BNP support voters, Begum Zia will lose the high moral ground she has been trying to take. One must also keep in mind that what we see as the BNP vote of 2001 includes the votes of Jamaat and the non-party swing voters. These votes will not transfer to JP(E). Then comes the question, what will the BNP gain? Ershad joining the Alliance does not mean the JP vote will transfer to the BNP. On the contrary, it will go to rebels, Independents, and marginally to AL. There is also the strong possibility that the JP(E) will again split. This splinter group may tie up with other BNP rebels to form their own electoral understanding. Even in North Bengal, including Rangpur, the JP(E) is on a slippery path. Kansat, Phulbari and other factors have changed the electoral scene from that of 2001. While the proposed alliance of BNP and JP(E) looks a win-win situation to the leaders of the two parties, to me it is a lose-lose situation. Not only that the JP(E) will not be able to win any seats outside Rangpur, even there the number of seats will decrease to a single figure. I do not see the Party winning more than 9 seats.

The Awami League

The Awami League is largest of the political parties. Though founded in 1949, its re-birth was in 1966 under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who became the Party’s President. He then presented his Six Point Formula for the autonomy of East Pakistan. This became the central principle of subsequent movements that finally led to the War of Independence and the birth of Bangladesh. That Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the father of this nation can never be in doubt, as all actions in 1971 were taken in his name. The Awami League framed the Nation’s first Constitution keeping in mind the people’s aspiration as reflected in the Independence War. But the change of Constitution through the Fourth Amendment, and imposition of one Party rule in the form of BAKSAL in January of 1975, divided the nation. This divide would continue for the next twenty five years. The subsequent events and years saw mixed fortunes for the Awami League. It did take part in the Presidential elections of 1978 and was mainly responsible for the 21.70% vote gathered by General M.A.G.Osmani. It participated in the Parliamentary elections of 1979, getting 39 seats with 24.55% of the votes. The return of Sheikh Hasina in 1981, and her assumption of the leadership of the Party, gave AL a new impetus. It decided to withdraw from the concept of BAKSAL by saying it now preferred to return to a parliamentary system as prevailing before the Fourth Amendment. It took part in the Presidential elections of 1981, and their candidate Dr Kamal Hossain managed 26.35% of the votes.

Its co-operation with Ershad in the elections of 1986 did not pay any dividends as the results of the 1991 elections show. However, its vote share continues to increase. As I said earlier, it has now overcome its BAKSAL negative image, but is yet to gain a strong positive one. One of AL’s problems so long has been that it did not have a viable electoral ally, one that could support it in an election arrangement. Its allies in 1991 could not help them, and these allies lost most of the seats they had got as their share. The present 14 Party Alliance really means nothing from a vote point of view as none of the other Parties have any electoral strength. Since the anti-AL alliance is based on the theory of accumulating all anti-AL votes into one basket, the AL needs a strategy that would reverse this. So long it did not have such a possibility. Now it has been gifted this opportunity by the new BNP leadership. What I mean are the BNP dissidents who are likely to float their own platform. The Awami League may take full advantage of this. The way this is likely to work is for the dissidents led by Dr Chowdhury and Col Oli, either collectively or from separate platforms, to put up candidates in as many constituencies as they can. Say in 100 seats. They will have an understanding with the AL in some 25 to 30 core seats where the AL will not put up any candidates. This would mean the return of the main leaders of the BNP dissident group. In the other seats, the dissident candidates will eat onto the BNP led Alliance vote bank.

Let’s look at a hypothetical scenario. Greater Chittagong District has 22 seats. In 2001, BNP, with 53.56% of the votes won 18 and the AL with 38.67% only 3. For all purposes these are safe BNP seats. Now, in a changed situation, Col Oli Ahmed contests in five constituencies. He wins in his own seats of Chandanaish (Ctg-13) and Satkania (Ctg-14) with AL help. He also contests BNP held Patiya (Ctg-12) where the BNP margin is 8,286, Ctg-11 (BNP margin 16,664), and Ctg-09 (BNP margin 19,721) and diverts a part of the BNP vote. Considering that the margins in question are less then 10% of the votes cast, and combined with other factors mentioned earlier, those seats could easily be won by the AL. This exercise, repeated in all the 22 seats would likely see reverse result from that in 2001.

The same scenario could work with Dr Chowdhury in the BNP strongholds of Greater Dhaka. For instance, Manikganj-02 is already lost to BNP. Manikganj-04 after the recent bye-election is precarious. Munshiganj-04 has a BNP margin of 7.46%. Similarly Dhaka-01 (Dohar) has a margin of 2,771 votes or 2.95% and Dhaka-02 (Nawabganj) has a margin of 2,544 votes or 1.81%. These are said to be BNP fortresses, but the Bikalpa Dhara is already inside it. The Awami League now has a unique chance to play electoral politics. Sheikh Hasina seems to recognise this need for electoral understanding, as in her meetings with her District Party leaders, she has prepared them for seat adjustments and sacrifices. It is now up to them as to how they handle this opportunity.

Like all major parties, the AL has its own problems of inner party conflict. Fortunately for them, their voter base is more loyal as it is founded on long time politics, and when in opposition, is likely to close ranks when it comes to voting day. Sheikh Hasina today has a historical opportunity before her. With more then half the voters dissatisfied with political parties, she is faced with a great number of undecided voters. It is now up to her as to how she attracts them to her party. Negative policies will not work. She has to state positive positions of her party. She has to say how she will govern if again voted to power. Mere party manifestos are meaningless. As it is, voters tend not to believe political promises. She has to read the mind of the voters and understand his or hers need. She needs to sense the mood of the nation as her father did exactly forty years ago. “People power” as demonstrated by Kansat, Phulbari, Demra, Mirpur and now countless other places, means that people want to actively participate in their own destinies. This nation can no longer be governed centrally from Dhaka. Sheikh Hasina has to promise power to the people. She has to promise decentralisation and effective local governments. She has to spell out how she will help the small trader and local business. She has to reach out with concrete proposals on economic policies or any other matter that affects the citizen’s daily life. Though the voter will view all political promises with scepticism, he or she is more likely to go with the opposition then the party immediately in power, for that Party will be judged more by their present performance. If the AL is able to attract even half the undecided voters, they will win the next election. If they are able to convince 55% of the undecided to vote for the Party, they will win by a landslide as large as that the BNP got last time around.

Others (Parties and Independents)

Normally, “others” are a reducing species, coming down from 34.29% in 1979 to 5.59% in 2001. I do not see any change in the next election. Small parties like JP(Manju) will align with the AL for a few seats. There will be a lot of Independents and fringe religious parties, but I do not think they will have any impact on the main game, except to hurt the BNP to some extant.

Summation

Election numbers are the most popular game at the moment. What I have tried to present is a view of the overall situation based mainly on factual numbers based on past elections, and my own perception of the present situation. We have examined the strengths and weaknesses of the different Parties. We have seen the regional vote patterns. We have looked at the new realities and changed equations. Based on all these factors I have indicated my opinion on the probable performances of the different parties.

To surmise, there are two ways of looking at the possible results. The first is based on the Survey. If we accept that there are about 53% voters undecided, the question comes as to which direction they will eventually move. The Survey shows the AL with about 23% of the vote and the possible BNP Alliance (BNP+JI+JP(E)) with 21%. It is the nature of election swings that the undecided, (in this case the dissatisfied), vote will be divided in similar proportions. However, one has to factor in the anti-incumbency element, in which case the balance will tilt in favour of the opposition. If the AL gets even just 52%, and “others” 2% of the undecided votes, it leaves BNP with 46%. A spread of 6% between the BNP Alliance and the AL would be a conservative estimate under the present circumstances. This means a grand total of 51% for the AL and 45% for the BNP Alliance, and 4% for “others”. In this scenario, the AL could theoretically win 300 seats. While the prospect of AL and partners getting close to 50% is a possibility, the actual seats they would win would be around 220 plus.

The second way is based on the results of the 2001 elections. In every election a party gets a certain vote share. As the political process of a nation consolidates, the major parties get the major share of the votes. Over the last three elections, we have seen the vote share of BNP and AL consolidate from 61% to 87%. As both these parties will lead major alliances in the next election, it is safe to assume their vote share will be more than 90%. The vote swing is represented the change of vote by a voter in one election to another party in the next election. Since 90% of the people are likely to vote for one or the other Alliance, it is safe to presume that 90% of this vote swing will go to one of the two parties. When a voter decides not to vote for the party he voted for the last time, it is an “outward” swing. In this close situation, the outward swing of a party becomes the “inward” swing of the other. Outward swings occur more from parties in government as they are the repository of a larger number of votes obtained in the previous election. This is the “anti-incumbency” factor.

In the 1996 elections, the BNP won 116 seats compared to 140 in 1991, although their vote share increased from 30.81% to 33.61%. The AL won 146 seats in 1996 compared to 100 in 1991. Their vote share increased from 33.33% to 37.44%. The increase or inward swing for both the BNP and AL was at the cost of Jamaat and “others”, whose vote share fell from 27.30% of the total votes to 12.72%. The 4.44% more votes that the AL got in 1996 gave them 46 extra seats. However, now that the vote is more consolidated and split among the two top Parties, any swing will be at the cost of one or the other. The higher the bracket of votes (say 40% and above) that the two Parties get; the closer will be the difference of votes between them in the individual constituencies. That means a greater number of seats will become “marginal” and will be decided by even small vote swings. The end result will be that the party which gets the highest number of votes will win a disproportionate number of seats

In 2001, the BNP Alliance got 47% votes. That is, 47 persons out of 100 voted for the Alliance. If 7 of these voters decide not to vote for the Alliance in the next election, it means an outward swing of 7%. Most of this outward swing will go to the AL giving them a theoretical total of 48% against BNP’s reduced total of 40%. How much is a 7% vote swing? It means that 47 voters out of every hundred who voted for the Alliance, just 7 persons (which is roughly 15% of 47) will not vote for it next time. Readers can now do their own sums. Do you think that every single person who voted for the BNP Alliance will again vote for it again? Will the millions of new voters vote for it in the same proportion? There you have the answer. If among all your friends, relations, colleagues and other people you meet, you find 10 persons who voted for the BNP Alliance, and of them, one (10%) says he or she will not do so next time, you have an outward swing for the BNP of 4.7% of the total votes (10% of 47%). You can do the same exercise for the AL. You will come up with interesting numbers.

Politics is not static. Everyday will bring in a new issue, a changed circumstance. However, if the elections are held as per the schedule, and all the major political parties take part, I do not see a different eventual outcome from that I have presented. For me personally, I see an outward swing from the BNP Alliance of around 8%. This will take the AL and their electoral partners close to 48% of the votes. Under these circumstances, I do not see the Greater BNP Alliance (with JI & JP(E)) getting more than 80 seats in the next Parliament. The AL share will be around 180 seats, with about 40 seats going to AL Allies, “others” and Independents.